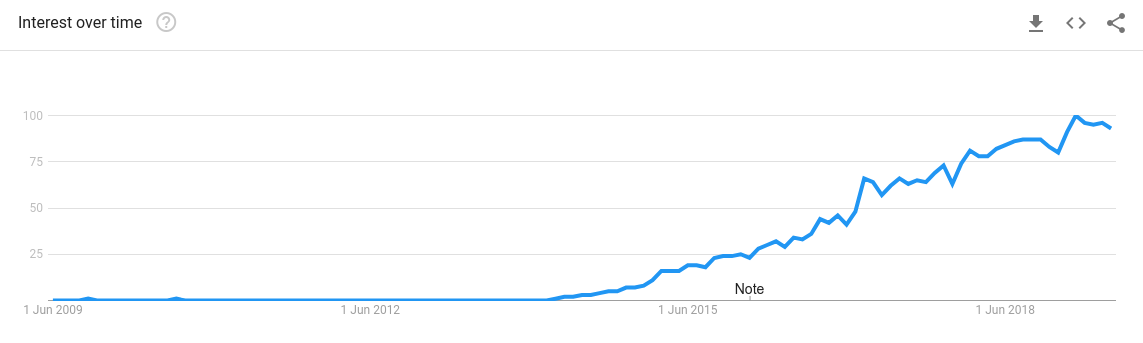

The microservices architecture has been one of the most popular terms in the software industry during the last years. Software development teams across the world have been working tirelessly for months in an effort to kill the notorious monolith and replace it with new, elegant & loosely coupled microservices that will help their business thrive. A few months or a couple of years down the line, they realise that something went wrong along the way and this new architecture has the adverse effects than the ones they were promised. They were made to believe that a microservices architecture will help them be more agile and deliver business results faster, but they realised the hard way this is not the case.

I have heard this story from ex-colleagues and friends many times so far. I believe the time has finally come to spend some time on thinking why this is the case. After all, the principles behind the microservices architecture are all sound, so where did we go wrong?

My personal belief is that this problem is rooted in various cognitive biases of the software engineering population. Everytime something new emerges in the software industry - whether that is a new technology or a new architectural pattern - people tend to get excited very easily and disregard any pitfalls. Because of the limited duration of human life currently, it’s also less likely for people to have extensive context on the history of software and similar or competing technologies/patterns from the past, so that they can make comparative evaluations. Another unfortunate fact is that technical people sometimes tend to be more interested on the technical than the business aspect of a problem. In the worst case, they might even prioritize the technical purity of a solution over its suitability to the corresponding business needs.

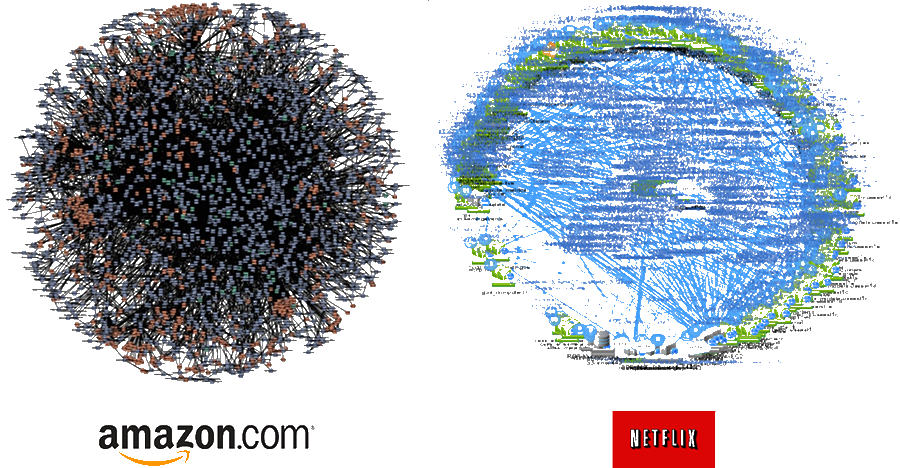

A few years ago, several big technology companies started sharing data and visual diagrams of their microservices architectures with the rest of the industry.

Looking at this image without the associated context, if someone asked me to describe it with a single word most likely I would choose the word complexity. However, “tech” people got really excited - instead of complexity they were seeing elegance. They viewed it as the pinnacle of software architecture, where responsibilities are split in such a good way between all these services that coordinate with each other to achieve collectively a business purpose. If these big companies are doing it, then why shouldn’t they? So, they started adopting this new architectural pattern, sometimes without even thinking whether that’s the right tool for the problem in hand.

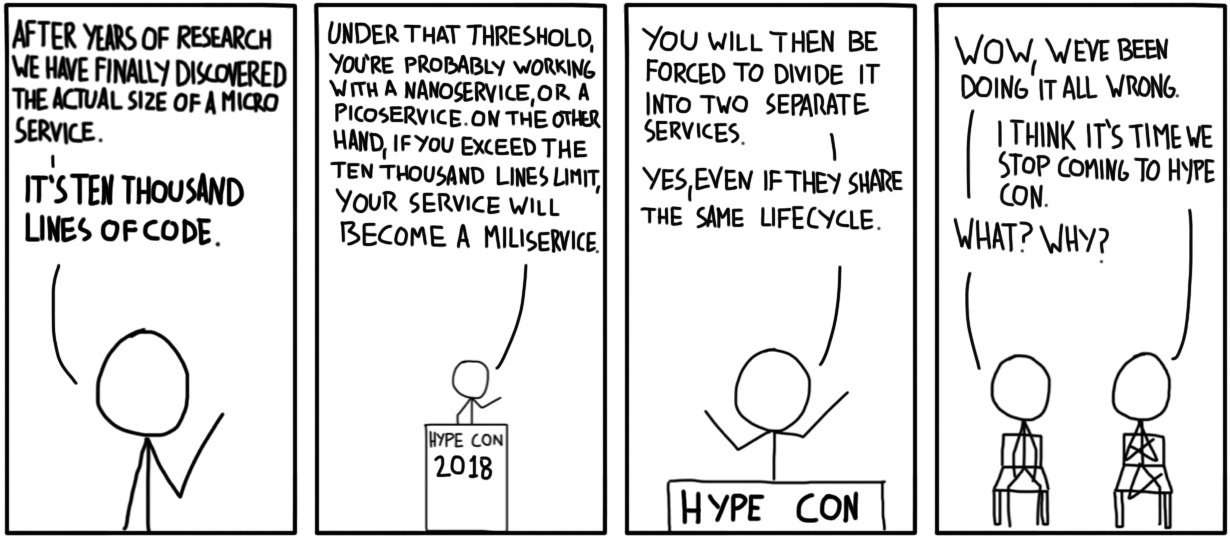

People started getting so obsessed with this pattern that at some point they started debating what is the right size of a microservice - sometimes even defining that in terms of lines of code…

At this point, one could easily see that something was going wrong - we could not see the forest for the trees. No matter how trivial that might sound, I believe that the name of the architectural pattern has done a disservice and contributed to this misdirected focus, especially the “micro” prefix. This was the trigger for this post and the motivator for the post’s title. Of course, microservices is not really a new thing, most of you already know about the service-oriented architecture, commonly known as SOA. I strongly believe this would be a much better name and would highlight better the principles behind it. Unfortunately, it was already taken.

This created even more confusion. Now, people are trying to understand what is the difference between microservices and SOA and draw boundaries between them. This is not what matters though. What you should care about is not whether your architecture should be called a microservices architecture or a service-oriented architecture - it’s whether it serves its purpose.

In order to achieve this, you have to make sure that the structure of your architecture is the right one; that you have defined the proper boundaries between your services and the interaction between them is as smooth as possible. An astute reader might notice there is an isomorphism between these 2 different questions:

- What’s the right size of a microservice?

- What are the right boundaries between microservices?

However, the first question focuses on the surface, while the second one focuses on the essence. The right question to ask is the second one. So, here are some of the things one should consider when thinking about the high-level architecture of a system composed of multiple services:

- Can teams be held accountable for the business results of their services? If boundaries are not selected carefully, then each service does not have a single, autonomous business goal and does not really provide value on its own to the rest of the services. An architectural smell pointing to this issue sometimes is inability to easily identify and monitor the business results derived from a service. This could be done either via runtime traffic monitoring, integration with an existing business analytics platform or with A/B testing infrastructure.

- Do the selected boundaries allow the corresponding teams to operate independently? The main principle behind the microservices architecture is to allow teams to move independently having as an ultimate goal more business agility in the overall organisation. In order to achieve this, services should be able to make improvements on existing functionality and add new functionality while minimizing the changes required in other services. That’s not something new: back in the days of three-tier applications, people were trying to decouple the front-end from the back-end of the application, so that new features would not require making the same changes in two places. It’s just a macro view of this general guideline.

- Are there any requirements around transactionality? The microservices architecture advocates encapsulating different datastores behind different services and advises against using datastores as integration points between services, which tends to lead to a lot of problems down the line. However, there can be scenarios where atomicity between multiple datasets is a very important business requirement. This requirement can provide valuable input on where you should draw a boundary. Distributed transactions between services is a minefield, but one can alternatively encapsulate all of these datasets behind a single service and offload transactional capabilities to a datastore that already provides support for this, such as relational databases.

- Are there specific requirements around latency? Every new service introduces an additional network round trip in the customer journey. Unfortunately, in this case “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”, because a jitter in one of these services can have a big impact in the customer experience. The more of these services you have, the more likely it is for at least one of them to misbehave at some point. I will never forget the war story of a company, where some engineers fell victims of over-microservices-isation for the sake of “a good architecture” ending up with an end-to-end latency of several seconds. After a serious re-architecting effort merging services, they finally managed to drop that to around 150 milliseconds! So, be aware of this and act accordingly.

- Is your architecture aligned with the skillsets of the associated teams? As I already mentioned, the main principles behind microservices were rooted in organisational and business concerns with significant inspiration from Conway’s law. If you want your teams to be as efficient as possible, then you have to make sure they are making best use of their skills. As a contrived example, you would not want people with expertise on Machine Learning to spend their time trying to figure out how setup a build system or create front-ends. This is another aspect that can provide valuable input in the architectural decision making.